Saturday 8th March 2025

The conference explored questions over successions from one leader or monarch to another.

What makes for a smooth succession? Does the succession of a monarch differ from an authoritarian leader?

Three lectures on Henry VII and James VI in the British Isles and Stalin in the Soviet Union.

This diverse programme served to foster many

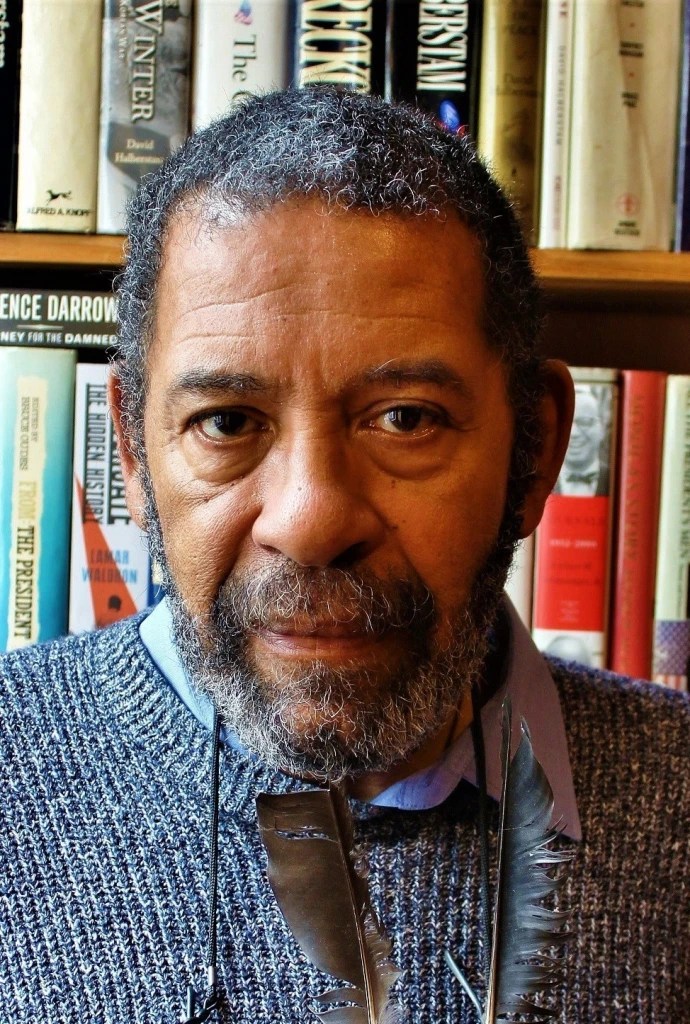

stimulating questions from a large and engaged audience. In his opening address, the Forum’s President, Dr David Smith, paid tribute to Nicolas Kinloch, a truly inspirational figure and stalwart of the Forum for over 40 years who died in 2024. He is deeply missed.

Prof Jessica Sharkey (UEA) ‘Did 1485 Change Anything?’

The first lecture was delivered by Professor Jessica Sharkey, Associate Professor of

Early Modern History at the University of East Anglia who is currently researching

how Tudor England encountered the world beyond Europe and how it used notions

of ‘the other’ to construct its own identity and purpose. Professor Sharkey addressed

the Forum on the topic of ‘Did 1485 change anything?’ and began her lecture with an

examination of the nature and impact of Henry Tudor’s victory at Bosworth in August

She noted the challenges of invasion and conquest, yet in winning the throne

on the battlefield, Henry was able to claim the endorsement of divine providence.

The English monarchy had been built on an unbroken line of succession, yet this

was challenged by the Wars of the Roses, with four kings being deposed. However,

having secured victory against the odds at Bosworth, Henry’s challenges remained.

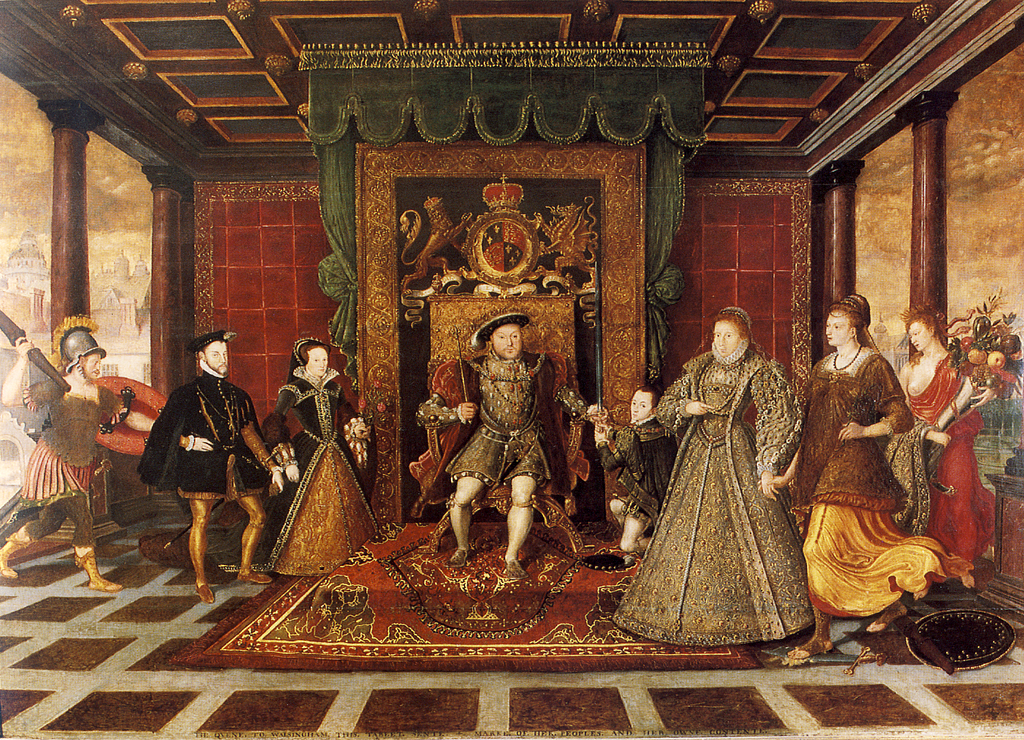

Professor Sharkey then looked at different aspects of Henry VII’s reign, a king who

had ‘lived on the margins’ and is often seen as marking the dividing line between the

Medieval and the Early Modern periods.

On winning the throne, there were a number of key considerations for Henry VII; he

needed to repel challenges from the pretenders Perkin Warbeck and Lambert

Simnel, who sought to play on the weakness of the new Tudor monarchy, and then

to secure his dynasty. To strengthen his position, Henry married Elizabeth of York

thereby creating the iconic Tudor Rose, whilst the subsequent marriages of their

children were used to create and strengthen foreign alliances. Professor Sharkey

argued that Henry VII’s reign was one of crisis management rather than innovative

government. In managing this ‘system’, Henry focused on involving a trusted few,

promoting ‘new people’ such as Empson and Dudley, a strategy which alienated the

existing nobility. For Henry, a rich crown was a strong and powerful crown; robust

finances brought security. Furthermore, he demonstrated a keen appreciation of the

performative dimensions of monarchy and was willing to divert considerable funds to

this effect, adding the Henry VII Chapel at Westminster Abbey. Other institutions

which benefitted from his largesse included King’s College, Cambridge and Eton

College. The closing years of Henry’s reign were beset with his own concerns

regarding the succession, so much so that his death was kept a secret from the

public for two days. However, this would prove a peaceful transfer of power, leading

Professor Sharkey to pose the question whether 1509 is not as important as 1485.

Dr Alex Courtney (Perse School) ‘Lost in Translation? James VI of Scotland as Elizabeth I’s successor’

For our second lecture, Dr Alexander Courtney of The Perse School, Cambridge

spoke on the topic of ‘Lost in translation? James VI of Scotland as Elizabeth I’s

successor.’ Dr Courtney has written a recently published groundbreaking biography

‘James VI, Britannic Prince: King of Scots and Elizabeth’s Heir, 1566-1603’ offering a

detailed account of James VI’s life, with a particular focus on his Scottish rule and his

path to becoming King of England.

The four hundredth anniversary of James VI and I’s death is an opportune moment

to revisit how we understand and assess his character and leadership. Erroneously,

James has often been presented as a marginal figure, hence his partial erasure in

the popular consciousness. However, negative sentiments towards James on his

accession to the English throne in 1603 have been exaggerated; he had many

supporters in the shires and there was widespread evidence of popular support.

James has often been the victim of a crude comparison with his predecessor, both

by frustrated courtiers and a later distorted historical tradition. For instance, he has

been much criticised for his seeming financial profligacy, yet by comparison,

Elizabeth’s frugality was scarcely virtuous or prudent. Indeed, James was more

accessible than his predecessor; his Council was broad unlike Elizabeth’s narrower

body. Furthermore, James is often presented as ‘foreign’, yet Scotland was far more

central in English calculations than is often assumed. Consequently, Dr Courtney

called for a more positive and less Anglocentric view of James. Scholars in England

often adopted an excessively negative approach, a stance originally framed by Sir

Anthony Weldon’s lurid and often homophobic character assassination of James

which has proved a primary cause of his corrupted image. By contrast, modern

Scottish scholars, notably Jenny Wormald, have focused on what was problematic in

England, inviting readers to reflect on English political culture and the structural

problems of the state, a stance which warrants close reflection. As Dr Courtney

pointed out, a truly British history of late sixteenth and early seventeenth century is

much needed. Fundamentally, it was Elizabeth’s problematic legacy rather than the

weaknesses of the new king which posed the greater challenge. Whilst Elizabeth

may have been highly adept at dealing with crowds, James was energetic in

promoting his views in print. For instance, he appealed to English readers before

1603 in attacking the Highlanders as barbaric. James’s preference for privacy was

perhaps a legacy of his childhood, one which could be described as vivid rather than

miserable. However, this preference for the company of a select few, often his

hunting companions, created a space for criticism, especially after 1619. Before this

point, James’s court was broad and inclusive but thereafter, became narrower and

diminished. The death of his eldest son Henry in 1612, the marriage of his daughter

Elizabeth to Frederick V, Elector Palatine in 1613 and the passing of Queen Anne in

1619 left him increasing removed and open to allegations of vice.

Dr Jonathan Davis (Anglia Ruskin) ‘Stalin’s Coming to Power’

Our final lecture from Dr Jonathan Davis of Anglia Ruskin University explored Stalin’s rise to power. Dr Davis has written widely on twentieth century Russia; his book Stalin: From Grey Blur to Great Terror (Abingdon: Hodder Education/Philip Allan Updates) was published in 2008 and more recently his ‘Historical Dictionary of the Russian Revolution’ (Rowman & Littlefield) in 2020.

Lenin died in January 1924, with no clear succession plan, hence the bitter power struggle which followed. Dr Davis traced the reasons for Stalin’s ultimate success ranging from interpretations rooted in party administration and ideology to the errors of his rivals. Ultimately, Stalin ‘played the game better’, but was far more than a simple manipulator holding deep convictions. Whilst others might win the argument, Stalin could win the vote. Thus, his success in the power struggle could be viewed as a triumph for organisation over reason. A series of strokes in May and December 1922, left Lenin weakened but still able to work, a period when Stalin increasingly became a key point of contact between the party and its leader. Fearing for the succession, Lenin laid down his views in his Testament, which promoted the idea of a collective leadership after identifying the perceived weaknesses of others, for example Bukharin’s supposed failure to appreciate Marxist dialectic. However, when Stalin offended Lenin’s wife, Krupskaya, a postscript was added to the Testament suggesting that Stalin should be removed as General Secretary. Lenin’s lack of a clear plan was undoubtedly significant, but even if he had been more decisive, Dr Davis argued that Stalin could well have circumvented this challenge. Trotsky later argued that Stalin manipulated events immediately after Lenin’s death, specifically the funeral, in order to present himself as Lenin’s natural successor. Stalin told Trotsky not to return for the event and according to Trotsky, even gave him the wrong date! However, the creation of the Cult of Lenin was important beyond Stalin’s rise; it served to shape the future nature of politics essentially tapping into religious culture. One may also approach Stalin’s rise from an ideological perspective. Stalin succeeded in isolating Trotsky and undermining his powerbase by presenting his rival as anti-Lenin through opposition to the NEP. Stalin also succeeded in exploiting conflict between Left Platform and Right Platform in promoting Socialism in One Country. By 1927, Stalin emphasised a war threat to justify industrialization and collectivization. His turn against the Right, which failed to appreciate the changing landscape, secured Stalin’s victory, and he strengthened his position further through the ban on factions. By 1929, Stalin was vozhd.

The Forum closed with a superb range of questions from the student audience which explored both individual and thematic responses to succession. Issues raised and discussed included strength of character, clarity of purpose and the manipulation of memory.